Football on the Brain: Helping coaches embed neuroscience knowledge

Written by

Simon Austin

March 2, 2025

“I’m an academic, but I use a lot more of my brain when I’m playing football than when I’m doing academic research,” says Holly Bridge, who is a Professor of Neuroscience at Oxford University.

This is why the qualified football coach decided to co-found Football on the Brain, a four-year public engagement project aiming to link researchers with football communities to help them understand more about the working of the brain.

“It doesn’t matter whether you are at the elite level or a six-year-old, you probably haven’t learnt anything about the brain,” adds Louise Auckland, a teacher and Impact Evaluation Officer who has also been leading the project.

Football on the Brain is funded by Oxford University’s Enriching Engagement Scheme and partners include the Wellcome Centre for Integrative Neuroimaging, Football Beyond Borders, She Kicks, Oxford United in the Community and Ignite Sport (Oxford City).

The project finishes next year and has already achieved a lot: the launch of a 10-session session youth module teaching how the brain is involved in football, a series of public information roadshows, and research projects on concussion and ball handling. Now the focus is on engaging the elite game.

“The final output is can we share research going forwards,” explains Auckland. “That’s why I came to your TGG Live Conference last year – to ask practitioners what questions they were interested in that brain research might be able to answer.

“How might the University department be able to support that or design research that may be useful to the footballing community? One of the aims of the project is to say, ‘what are the unknowns, because they could be areas for future research.’”

During the course of my chat with Bridge and Auckland, I asked them a number of questions about how neuroscience knowledge and research could impact coaching practice. We spoke for 90 minutes but were only scratching the surface.

Bridge has been playing football for 30 years and coaching for almost as long. She currently coaches a boys’ Under-15 team and says she’s noticed that coaching courses increasingly focus on sessions being ‘fun and gamelike’, but wonders if this has gone too far.

She says: “When I do the coaching courses, there’s a lot of moving away from repetition, because they want it to be fun and gamelike but, actually, the only way the brain can improve is by repeating things again and again. It’s just about making sure that what you’re repeating is right.

“An area of the brain called the cerebellum takes information from everything – senses, proprioception – and that is fed into your motor output. You predict what is going to happen and put that together with what actually happened.

“The cerebellum is involved in the automation of these actions. If you make a mistake that’s fine, because you recode it. What you don’t want to do is do something wrong over and over again and be told its right, because it’s really hard to unlearn that, as you’ve strengthened those neural connections.

“Repetition is everything. ‘This is the pass I did. Did it get to where it needed to be?’ If the answer is no, then you reduce the strength of the connections. You then do something a bit different next time and if you start doing it right, you embed that correct movement into your brain and the pattern of firing in your brain, so things become automatic.

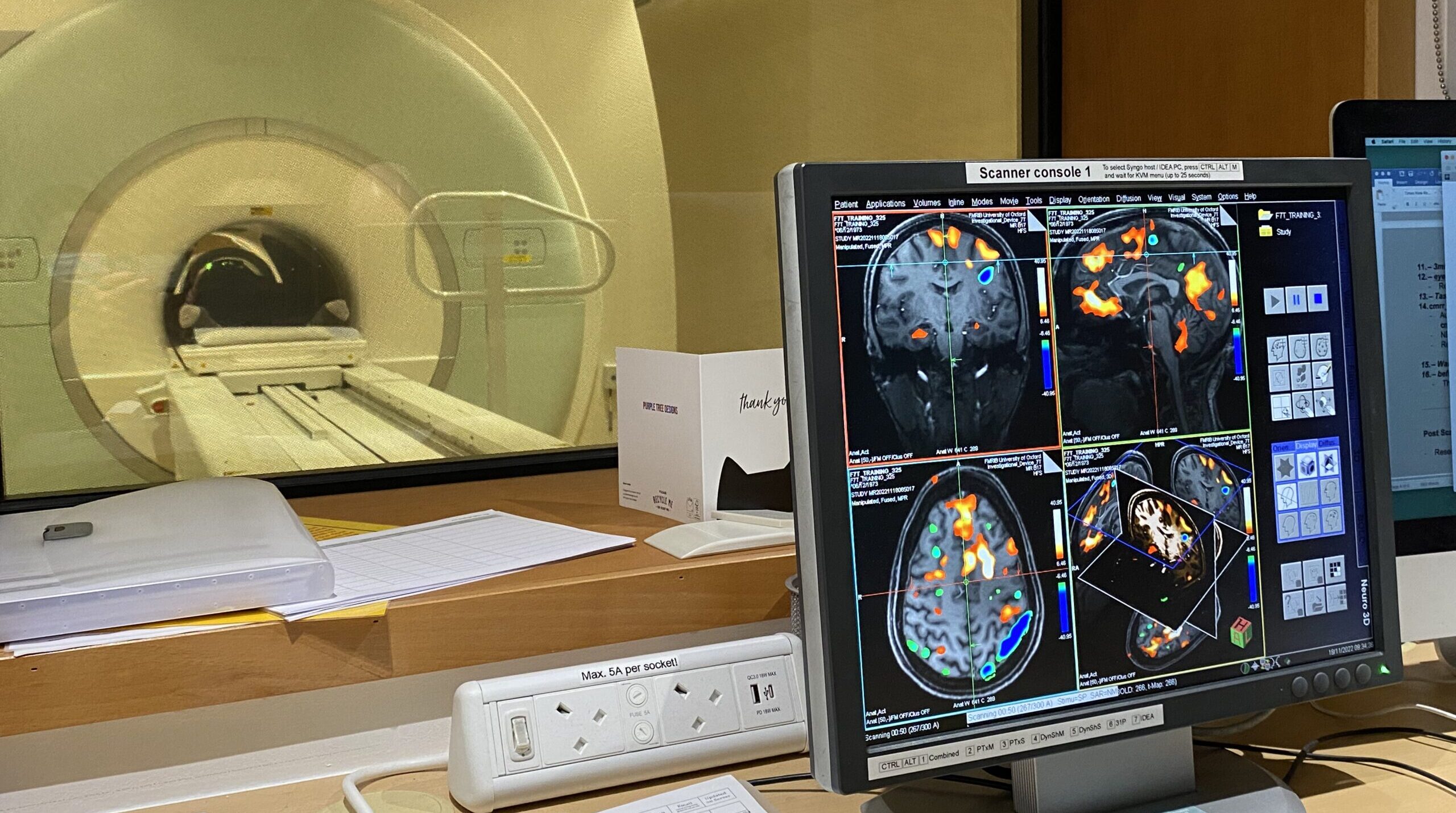

Football on the Brain have used brain scanning to investigate concussion and more

This thinking that all training should be ‘gamelike’ has been prevalent, which means that the use of cones or mannequins, or training tools like the Soccerbot, are sometimes frowned upon.

“The difference with mannequins is that people move in a game, of course, but until you can do that (dribble around a mannequin) you won’t be able to dribble around moving people,” Bridge says. “So it’s a building block.

“You’re going back to basics and reinforcing fundamental skills. Without doing it with mannequins or cones you can’t do it with people. You can automate your basic skills and that then frees up resources in your brain to recalibrate.

“There is a much broader area of changing team-mates or playing on a different pitch at a different stadium that require recalibration, but you still need those fundamentals of technique.

I’m often surprised at how few clubs work on self regulation and self awareness.

Louise Auckland

“The question is how much resource do you have? You could argue that professional players have a lot of time on a daily basis. So if you can work on aspects away from the football pitch, on something like the Soccerbot, I don’t see that that’s a bad thing.”

Football on the Brain have included a section on the adolescent brain in their youth module. Experimentation and creativity is a strong driver at this age, as is the visual.

“If an adolescent watches his or her peer do a trick or skills, there are mirror neurones that will activate,” Bridge says. “Then, when you try it with the ball yourself, they already have a head start.

“’You will have heard about dopamine and this is released when you get an unexpected reward. That is used in motivation to make you want to go and do it more. The brain likes novelty and unexpected reward.”

The project has also been looking at self awareness, self regulation and bodily state for players.

“I’m often surprised at how few clubs work on self regulation and self awareness,” Auckland says. “You can practice being aware of where your attention is in a particular moment and then developing the tools to zoom in or out or move it. Then you are able to skilfully respond in a moment.

“The brain has that limited capacity to process information, so where is your attention? Is it on the crowd, a parent, your team-mate, your feet as you haven’t automated that technique?”

“You need optimal arousal, so you’re not stressed but you’re also engaged. To know where you are on that requires practice. The difficulty for coaches is that it will be very different for every player on the pitch, because everyone has a different background, a different level of skill, a different level of shit going on in their life.”

The ultimate aim for a player is to be in the moment, able to adapt and respond to the state of the game.

“We could live like a crocodile – if you see something, move your jaw to it,” says Bridge. “Like if you overcoach players and they don’t adapt. It’s really good to have automation for basic skills, but you need to be in the moment, so you can actively make good decisions.”

We’ve written a lot on TGG about red and green states, with red “being tight, inhibited and anxious” and blue being “calm, clear and accurate.”

However, Auckland says: “You need optimal arousal, so you’re not stressed but you’re also engaged. In many ways you don’t want to be red or green, you want to be in the space where you can use the motivation of the stress response to drive your performance but not hinder it.”

Bridge adds: “There are two reds – one where you are in the zone and ready to kick the ref and the other where you’re just not up for it. To get into the green you need to be sufficiently aroused but not go over the top.”

If you want to connect with Football on the Brain and discuss how their knowledge and research about the brain could impact your coaching practice, then please contact Holly Bridge on holly.bridge@ndcn.ox.ac.uk

Professor Bridge and Louise Auckland are TGG Members and part of our Slack Community. To find out more about becoming a TGG Member, click HERE.

Follow Us

For latest updates, follow us on X at @ground_guru