Matthias Lochmann: How Germany revolutionised the foundation phase

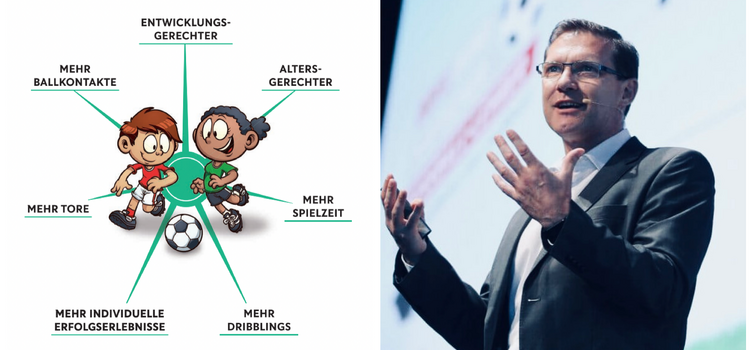

Clockwise from top: 'Developmentally fair, age appropriate, more game time, more dribbling, more individual success, more goals, more ball contact.'

Written by Simon Austin — August 6, 2022

IN March this year the German Football Federation (DFB) announced a revolution in the way that the country's Under-11s would play and be coached.

Gone were conventional 7 v 7s; in were small-sided games, four goals and shooting zones. The emphasis was on fun and a player-centred approach, with adults banished to supporting roles.

The DFB issued press releases and fliers detailing the changes, but two key figures were notable by their absence. The first was the late Horst Wein, who had created the concept of Funino (fun + child in Spanish), upon which Germany's new game formats were based.

The other was Professor Matthias Lochmann, who had provided a scientific basis for Funino and lobbied hard for the DFB to adopt the concept for the last seven years.

Lochmann will be the opening speaker at TGG’s Youth Development Conference in Manchester on September 20th, outlining the changes in Germany's foundation formats and the reasons behind them. Before that, here's the story of how he drove a major change in the way Germany will coach its young players.

Lochmann was a player at SV Darmstadt in the German second division in the late 1980s before moving into coaching, starting off as U15s lead at Mainz when Jurgen Klopp was a senior player and future manager there.

Professor Matthias Lochmann will be the opening speaker at our Youth Development Conference in Manchester on September 20th. We have a fantastic line-up of speakers including: Alex Inglethorpe (Liverpool Academy Director), Gregg Broughton (Blackburn Director of Football), Charlotte Healy (Man Utd Women's Academy Manager), Iain Brunnschweiler (Southampton Head of Technical Development).

A watershed moment arrived in 2000, when he attended a presentation by Wein, the former international hockey player and coach who had become something of a football missionary. Wein's Funino concept was billed as 'street football for the 21st Century' and involved small-sided games, four goals instead of two and small pitches.

What Lochmann liked was the fact that Funino involved not only more game time and touches - “reducing the size of the teams gives more ball touches, this is not rocket science" - but game intelligence as well.

"A player who is intelligent goes through four phases," he explains. "First you have to observe the environment. Then you understand what is going on. Then you make a decision. Then you execute. Most training exercises focus only on execution, but to have game intelligence you must be successful in all four.

"Funino addresses all of these areas and I thought, 'What will happen if we do this for three or four years with the youngest players? We will have players with really good technique who are able to make the right decisions.'"

Then life took over, as it so often does. Lochmann got a job as Professor at the Department of Sport Science at the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, where he still works today, and also started a family. His football coaching took a back seat for a while, until his passion for Funino was re-ignited when he began to coach his son’s team in 2015.

“My son was five or six and we started off with our team in the official league, 7 v 7,” Lochmann recalls. “This was a big mistake, because the children weren’t getting many touches and, even worse, they were on the bench and not even playing. Often they were crying or sitting eating sweets.

“I knew that unless we changed we were going to lose more and more children to the game. We were already having an increase in the drop-out rates for children aged seven, eight, nine and 10 in Germany."

In England we often look admiringly at Germany as European football's powerhouse, with their four World Cup trophies and three European Championships, but Lochmann saw things differently.

"Germany has a population of more than 80 million," he says. "Belgium (11.5m) has a smaller population than the state of Bavaria (13m) but a much better efficiency at producing world-class players. You have to ask why this is and I think it goes back to the way the children play the game at the youngest ages.

“At the front of my mind was Horst Wein and Funino. I knew we needed a revolution.”

So Lochmann took the team out of the league and instead they played small-sided games based on the Funino format.

“We now had three mini pitches in the same area that we had used for 7 v 7 and we were able to involve all of the children. They all had more touches of the ball, they all scored goals, they all developed their technique and all developed their decision-making. And, most importantly of all, they were all enjoying playing football."

There were tweaks to Funino, such as a shooting zone that players had to be inside in order to score. And there was a 'self-pass rule' to replace throw-ins, enabling players to pass or dribble back onto the pitch from the sidelines. All the rules were designed to develop game intelligence.

“Players have two attractors - the ball and the goal,” Lochmann explains. “If you use the conventional two goals then players always go to the centre and not the sides of the pitch. With two goals to shoot at they use the full width and have an added layer of decision making.

"The shooting zone creates more touches and playing culture. You can go into the shooting zone by passing or dribbling, so we see more decision-making and problem-solving. With the self pass rule there is a degree of freedom. If your team-mate is free, then pass to him; if not, you can dribble on. This rule was implemented in hockey 20 years ago and now there is even a discussion about implementing it into adult football.”

Lochmann says the Funino format also fundamentally changes the role of the coach.

"A lot of people still think the coach has to permanently explain things from the side of the pitch or before an exercise," he says, "but the coach should invest more into thinking about the rules of the game and allow the rules to do the job.

"Then the coach focuses on observation and during a break can talk about the good and bad things and evolve the game."

Buoyed by the success of the new format, Lochmann decided to spread the word. Ulf Schott, a former team-mate at SV Darmstadt, was working at the DFB as a Director (and is now Head of High Performance Programmes at Fifa). so Lochmann decided to go and see him to present his findings.

Specifications for the DFB's new game formats. 7 v 7 isn't permitted until the U10s and U11s.

“Ulf was impressed and said, ‘How do we implement this in Germany?’ I said, ‘Let’s do a pilot league.' So we started in Erlangen and then went to Munich, Hannover, Hamburg.”

Being an academic and a sport scientist as well as a coach, Lochmann was eager to gather data and video to back up his belief in Funino.

"We started a scientific study in 2015 and analysed the number of ball touches, the number of ones v ones, how many shots and dribbles, heart rate and GPS," he remembers. “The new approach had advantages over the traditional one in every aspect. You could see it with your own eyes, but the science backed it up.”

Still, there was resistance to change both from within the DFB and also the grassroots game.

“Inside the federation there are two factions - the sport side and the administrators," Lochmann explains. "The administrators said, ‘We have a good system, why change?’ I was on the outside, so I wasn't afraid to tell them why.

“If you want to innovate you have to be honest and not play tactical games, although innovators are often not embraced or involved."

Fortunately, there were a couple of big breakthroughs.

One came when Lochmann presented his findings to a Pro Licence cohort including Damir Dugandzic, who was a co-ordinator at the DFB and the future Technical Head of their Talent Development Programme.

“Damir asked if I could come to a small group of soccer association people and demo this in theory and practice,” says Lochmann. "We showed them the findings of the research and we also showed them on the pitch, with young players, to compare the old and new system. They could clearly see the difference."

The biggest turning point came in August 2018, when he was asked to deliver the keynote speech at the DFB’s International Trainer Congress in Dresden. You can watch a video of the presentation below.

The backdrop was Germany's humiliating exit from the first round of the 2018 World Cup and the U17s finishing bottom of the Torneio Internacional in Portugal. Suddenly there was an appetite for change.

“There were 1200 coaches from all over the world at the Congress and some of the most senior people from the DFB were on the front two rows,” Lochmann recalls.

One of them was Hansi Flick, who had been assistant manager of the German national team from 2006 to 2014 and DFB Sporting Director from 2014 to 2017.

“When I had finished my presentation, Hansi came straight over to me and said, ‘We have to implement this in Germany.’”

After this, things moved pretty quickly. The DFB introduced a two-year pilot of the new formats in the 21 regional associations and in March it was announced that they would become mandatory from the start of the 2024/25 season.

Lochmann is proud of his contribution, although he insists that most of the credit should go to Wein, who died in 2016.

“I put the things together from Horst and added scientific value, but the core idea is from him. He was the pioneer.”

-1.png)