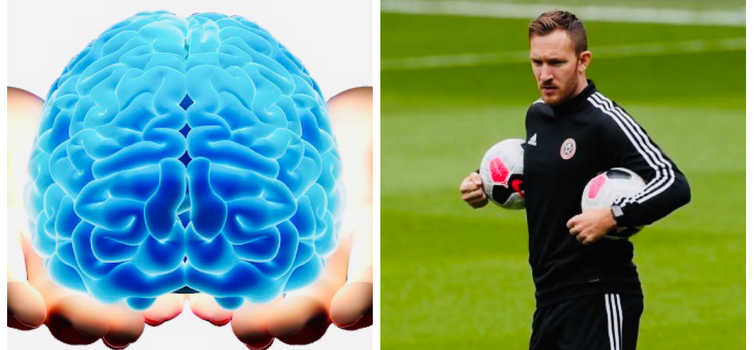

How new Development Coach roles are backed up by neuroscience

Rhys Carr has been Individual Development Coach at Sheffield United since September

Written by Dr Perry Walters — May 14, 2020

A number of Premier League clubs have recently appointed ‘development coaches’ tasked with working with younger pros and optimising their abilities and potential.

Liverpool, Southampton and Sheffield United are among the clubs to have recruited for this role, which takes a ‘360-degree’ approach to the development of young players who have just made the step up from Academy to first-team football.

Rhys Carr, who was appointed to the role by Sheffield United in September, described his remit as being to “give them (the young players) that little extra attention and detail that they need.”

These emerging coaching roles are prescient, because they chime with the latest findings from developmental neuroscience, which suggest that late adolescence (18-22) is a unique time for learning and development.

The science

Research has found that the late adolescent brain is both more plastic (adaptable to new information) and more sensitive and vulnerable to negative emotional environments than a mature adult’s.

Adolescence has been described as the ‘second window of opportunity’, because it offers potential for learning that is equally as important as in the first few years of life.

A 2016 UNICEF symposium suggested that this window could be optimised and kept open for longer in order to grasp the unique potential of the late adolescent phase of learning.

Traditionally, football has viewed the earlier development phases as THE time for exploration and experimentation and accordingly offered freedom for players to express themselves and make mistakes.

In contrast, this freedom has tended to diminish as players mature, with a greater emphasis placed on structure and results in the Professional Development Phase.

However, emerging research from developmental neuroscience has suggested that exploration, risk-taking and problem-solving could be equally as valuable for late adolescent players as for the younger age groups.

The plasticity of the brain - that is, its ability to change, rewire and adapt to new environments - is most pliable during this late adolescent period, particularly in the frontal circuits.

Late adolescence is a time of enhanced learning, where the brain is at its most efficient for information gathering, primed to seek out new experiences and learn better from them.

The brain repeats choices that are successful (accompanied by the release of dopamine) and learns not to repeat actions that are unsuccessful (accompanied by a reduction in dopamine).

This suggests the key for coaches is to create conditions where late adolescents are free to sample the environment and learn from their mistakes.

Individual development

Carr has said: “If you are in that group of players who are young but not involved in the first-team squad, then where is your development coming from? Games come thick and fast and training can be just ticking over. Where is the development going to come?

“I always use the example of a winger. Their job is to beat a man and get crosses in. But if they are only ever doing small-sided games in training, when are they ever facing up a full-back in that area of the pitch? They are not.”

This is where the individual development coach comes in. Working with young professionals to push their boundaries and extend their abilities can harness these natural instincts and motivations.

If clubs can create developmental learning environments for young first-team players, this might keep the window of opportunity for development open for longer.

Neurons are still firing at a faster rate (phasic firing) in the late adolescent phase of development, but this window of opportunity for learning begins to close if insufficient novelty and stimulation is provided by the environment.

When the environment becomes less nurturing, this heightened period of developmental plasticity decreases, and neural circuits mature, or settle down.

The rate of firing for dopamine also slows when the environment is less challenging, less novel or less developmental. If the environment is just ‘ticking over’, then clubs are potentially missing out on an opportunity to develop players during this ripe period for growth.

If clubs can create developmental learning environments for young first-team players, this might keep the window of opportunity for development open for longer, which is why these new development roles appear particularly appropriate.

Learning environments

Although an 18 to 22-year-old player might look like an adult, they might not be thinking, feeling and acting like one.

Harnessing the unique potential of the late adolescent period requires subtle changes in coaching methods. Coaches need to be mindful that these players learn through taking risks, testing abilities and pushing boundaries.

Creating secure, caring, non-controlling environments - where learners are empowered and have choice and volition - is often most effective.

Research has shown that in negative emotional environments, the late adolescent brain doesn’t function in the same way as an adult’s, but reverts to mid-adolescence type processing, characterised by unchecked, heightened emotions.

As such, supportive environments that facilitate instrumental, trial-and-error practices, where players can experiment and are free to learn from their own feedback, honour these natural drives.

Coaching conditions might take the form of ‘boundary work’, where practices are constructed to extend players to the edge of their abilities and test limits.

They might include, for example, crossing at full speed for overlapping full backs, or central defenders driving out from the back, experimenting when to pass and when to run with the ball.

Research also suggests a re-positioning of the traditional role of the coach towards more of a facilitator, or co-participant, in the learning process rather than a director and transmitter of knowledge.

This suggests a potentially difficult shift from the traditional role of the coach, with them ‘stepping off centre stage’, to more of a ‘co-participant’ role. This challenges some of the traditional assumptions about the role of the coach and the nature of learning, although it seems that views could be changing.

Huddersfield Town manager Danny Cowley recently told this website: “We try to encourage the players to become independent learners and take the role of a facilitator rather than a dictator. I personally prefer that style and I think the players learn better in that style.”

Cowley is a former teacher and his view chimes with the view of sports coaching as education rather than training, linked to the aims of developing inquiring and curious learners rather than technically proficient, passive receivers of knowledge.

- Dr Perry Walters is an Honorary Research Fellow at Bristol University and a performance coach at Bristol City Academy.

-1.png)