24

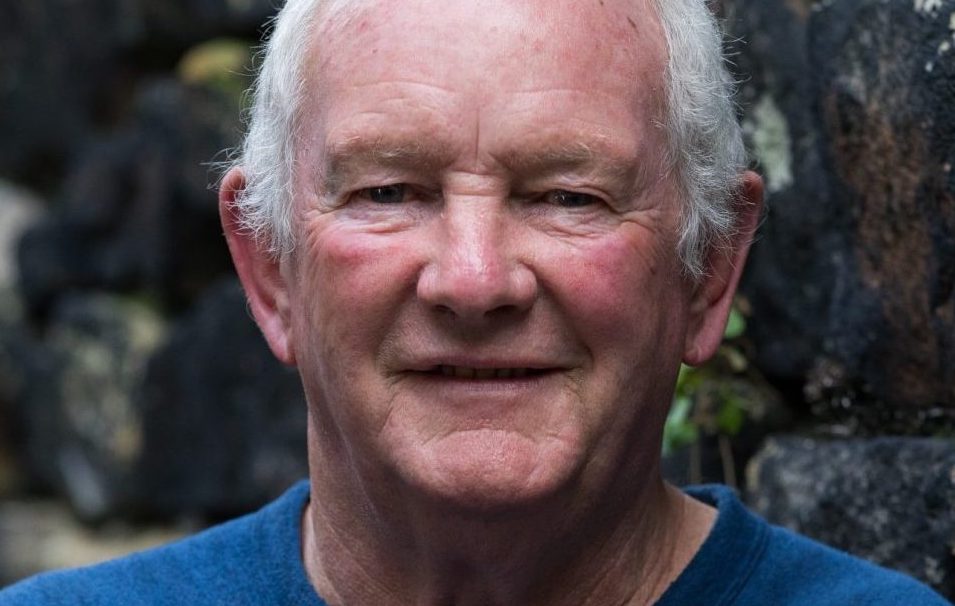

Brian Ashton

Lessons from a life in coaching

March 9, 2021

OVER the course of five decades, Brian Ashton MBE has forged a reputation as one of the finest coaches and coach educators in this country.

He led Bath Rugby during their period of domestic dominance in the mid-1990s, was attack coach under Sir Clive Woodward before they won the 2003 World Cup, and then took the side to the final of the competition himself four years later.

Since leaving the RFU in 2008, Ashton has been a mentor and coach educator for the Premier League, working with coaches at clubs including Manchester United, Everton and Manchester City.

The 74-year-old was our guest on episode 24 of the Training Ground Guru Podcast and told us about the lessons he has learned from a life in coaching.

1. Command-control doesn’t work

Brian Ashton: If you were to ask me to describe myself as a young teacher – I started in 1969 at a secondary modern in Preston – and as a young coach, I would say I was very much command-control, authoritative and dictator-like. Basically, I told the players what they had to do.

That was at odds with the way I played the game in those days, which was pretty non-conformist. I’m about 5 foot 6 and a half and was 11 stone wet through.

There were still some big lads knocking about in those days, so I had to use a bit of wit, imagination and invention to keep out of their way. I had to play in a way that not everyone else played.

But I kept coaching in this command-control fashion, without much success, and I taught the same way. A lot of young coaches and teachers go down the same route to begin with. The biggest factor in that is the fear of not being in control.

2. Coaching the reality of the game

This changed for me in 1975. I had just come back as a player from the England tour of Australia and was almost 30. I got myself the opportunity to play in France for a couple of years and then out in Italy, which is where I met a guy called Pierre Villepreux.

He was the French full-back in the late 1960s, early 1970s, before becoming Technical Director of the Italian Rugby Federation.

We became close friends and I was absolutely fascinated by his philosophy, which was all about problem solving, decision making and setting scenarios for the players to interpret and solve. It was very much player-engaged, dual leadership.

Rather than coaching isolated drills and techniques and putting together systems and structures, Pierre’s approach was more akin to the reality of the game, the fluidity of the game, the rhythm of the game.

It was decision making in the moment, instead of waiting for instructions from the touchline or at half time.

When I came back to England in 1980 I kept up the connection and it was Pierre’s influence that made me realise there was a different way of coaching – and it was a more effective way.

3. Player ownership

Once the whistle blows, the people who are in control of what happens next in the game are the ones out on the field. You can be the most magical coach the world has ever seen, but the impact you can have once the game has started is very limited.

I think I’m right in attributing this quote to Pep Guardiola about three years ago – ‘once the players cross the white line they’re in control of what happens next,’ which is very much the case.

However, I have certainly come across players at all levels that want to be told what to do – and that continued right the way through to coaching at senior level with England.

Maybe in the back of their minds they thought that if things went wrong they would have somewhere else to look – ‘I was just following a gameplan someone else put together.’ That has always struck me as a bit of a nonsense to be honest.

So the players have got to take some sense of responsibility. But as a coach you have to allow them to take this responsibility and to lead in preparation.

You can’t expect players to take ownership, responsibility and leadership by clicking your fingers on match day – ‘Right, you lot are in charge now, even though I’ve been in charge all week and not allowed you to say anything.’

4. No plan survives contact with the enemy

It’s very difficult to predict from minute to minute what’s going to happen in a game, so there’s a lot of volatility.

There’s a good old military saying – no plan survives its first contact with the enemy. I’ve been in plenty of games as both a player and coach where that has very much been the case.

After 10 minutes, you’re thinking, ‘wow, this is not what we expected.’ That could be for a whole variety of reasons – the opposition going through a purple patch, the referee interpreting the game differently to how you think it should be, players getting sent off, your best player going off injured. There are a million and one things that happen in the middle of a game that you just can’t predict.

If the initial way that we thought we were going to play isn’t working, what’s Einstein’s definition of insanity? Continuing to do the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result.

Do you keep following the plan and get to the end of the game and say, ‘oh, we’ve lost’? Well why didn’t you change the damn thing halfway through?!

Unfortunately, a lot of coaching, in my experience, doesn’t allow that to happen in terms of preparation. We prepare to play like this, we don’t prepare for ‘what if this doesn’t work?’

We don’t look at the worst-case scenarios and whether we have the tools and resources to be able to switch direction in the middle of a game and play in a different way.

5. Everyone needs to get their hands dirty

I’ve often been described as a maverick coach, which I object to, because mavericks are people that do their own thing and have no regard for the greater good of the team.

For me, the maverick is one who doesn’t want to get his hands dirty when things go wrong. In a team game, everyone has to have that desire and passion to say ‘we’re in trouble here, we’re going to dig our way out of it.’

For me, the maverick isn’t the guy with the x factor, it’s the disruptive player who doesn’t want to get involved when things go wrong. ‘I don’t want to dirty my hands with things that are below me.’

6. It’s ok not to know the answer

Some coaches don’t allow time for questions, like I didn’t during my first 10, 15 years in coaching and teaching.

In the classroom, I was the guy with the degree, I wore the gown; on the coaching field I was the one in a tracksuit with a clipboard, very often with a load of rubbish written on it, and a whistle round my neck so I could interfere with practice whenever I felt like it – in fact I became one of the chief whistle blowers in the North West of England.

It’s that fear of being asked a question you don’t know the answer to. There’s nothing wrong with that, nobody knows everything. But it’s getting your head round that, it’s having that mindset ‘we’re all here to improve together, it’s not just about me, it’s not just about you guys, it’s about both of us.’

So logic dictates there’s got to be two-way conversations and they’ve got to be allowed to ask questions as well, ‘why are we doing this?’

It’s not only me asking a player ‘why did you do what you did?’

Coaches can learn from players as well as players learning from coaches. They’ve got a different perspective on things, they see the game in a different way out on the field than you do stood on the touchline or sat in the stand.

They very often pick up on cues and emotions in the middle of a game that you just don’t feel. It’s really important to engage and listen to what they’ve got to say.

It doesn’t mean they’re dominating the environment, but for me it means that as a coach you’re playing a far more influential role in improving the group if you actually engage and listen to their ideas and thoughts.

If the players feel there’s a better way of doing things or we’re not doing it the right way, why shouldn’t they have a voice? We’re all in there to help the team get better.

7. Respectful challenge and vibrant families

Thirteen months ago I was in Australia and talking to John Eales, who captained the 1999 Australian World Cup winning team and we were talking about team cultures. He said they built up a culture of respectful challenge, where the coaches challenged the players and the players were allowed to challenge the coaches providing they did it in a respectful manner as well and that went right the way through the organisation over a period of time.

He said it created what he called a vibrant family and family for most people is the strongest bond they ever feel in their life, far stronger than a team. The vibrancy was the fact that this respectful challenge was allowed with a view to continually improving the way they performed.

I always felt when I was in a position as head coach, head of department, whatever, that I was accountable. But you can’t be accountable for everything. You can’t be accountable for things that happened from minute one to 90 in a match, you can’t be accountable for somebody missing a penalty, that’s not your fault as a coach.

That’s just a ridiculous notion and a lot of it is driven by the media and people who don’t know a lot about coaching.

The guy at the top has to be accountable, but the people who play the game have got take responsibility for their roles and how they function in the team.

8. Sticking your ego in your back pocket

I’ve never been a fan of coaching award courses, because it always struck me they tried to clone you. Being non-conformist, that’s the last thing I want to be in my life, a clone.

Being involved with Bath rugby from 1989 to 1996, that was a seven-year coaching award course for me in real time. I learned so much from that environment, from those players, about coaching, how to involve players, how to listen to players, how to challenge players.

They were like a rock and roll group, they were pretty non-conformist themselves. They didn’t like doing things that other teams did, they didn’t like playing in the way other teams did, they always wanted to be moving on. And they hated sessions that were repeated and jesus, they had memories like bloody elephants.

I’ll never forget the night we had a session I felt had gone pretty well. I got everyone together, ‘ok, anyone got any comments?’

Jerry Guscott said, ’Is that all you could come up with after two days of planning? We did that three weeks ago.’ And he walked off, leaving me with a group of 22 players, most of whom were internationals.

As I was driving back I reflected on what had happened and he was absolutely spot on. Here are these guys, some of them having travelled quite a distance turn up for session that was pretty close to a repeat of what they’d done two weeks ago, and they’d done it successfully and done it well, and his point was why do we still do things we can already do? It’s a really interesting coaching point that.

One of the things I learnt very quickly was you stuck your ego in your back pocket and zipped it up. I was surrounded by players who played international rugby and some of them knew far more about some elements of the game than I did, so it would have been foolish not to engage with them.

9. Beware the culture of the coach

What I’ve never believed in – and I think this is a real danger – is the culture of the coach. The game’s not about the coach, the game’s not about the manager, the game’s about the players.

They’re the guys that go into the battle arena, they’re the guts that make decisions in that 80 or 90 minutes plus that are ultimately going to decide how the game unfolds and, for me, we need to recognise that.

At the top levels of the game, the players will have a certain amount of knowledge and it’s good for them, now and again, to be in charge of a session.

So let’s say the forwards want a scrummaging session – well, let them run it. When I played back in the 1970s for Lancashire, the guy who ran the scrummaging session was a prop forward called Fran Cotton, who had captained England, gone on Lions tours, and who had a phenomenal rugby brain. He could take sessions like that.

Nowadays the coach seems to have become far more important.

10. Fail fast, learn fast, fix fast

My mentor is Kevin Roberts, the ex world chief executive of Saatchi and Saatchi, and he has a great phrase – fail fast, learn fast, fix fast.

In a sporting context that is particularly important, because the games don’t last that long, so you can’t be repeating the same mistakes over and over again.

I’ve also always been a big believer in situational leadership – you lead according to the situation you find yourself in. Sometimes you can be very direct and confrontational, other times you step back and let things happen.

I’ve got no idea whether I’ve got the credit I deserved as a coach or not and, to be honest, I don’t really care.

I know what I’ve done, the people who I’ve coached know what I’ve done. I didn’t get on with everyone, but I think that’s just the nature of life.

Not every player liked the way I coached, just as I didn’t like the way a lot of the players played, but that’s just the way life is.

This content is for TGG Members

To view this full article (and all others) you need to be a TGG Member. Join up today and also get access to:

- Masterclasses & Online Conferences

- Full Academy Productivity Rankings & analysis

- Club Directory with 96 clubs & 1,000+ staff profiles

- Personal Profile Builder to showcase yourself

- TGG Live 2024 & 2025 presentations