How top clubs are leveraging blood data

Written by

Simon Austin

December 11, 2025

Biomarkers are the body’s equivalent of the lights and dials on your car’s dashboard, revealing what’s going on beneath the bonnet.

If there are alerts, then skilled Sports Scientists, like mechanics, can set about diagnosing problems and recommending remedial action. As well as helping to avert illness or injury, biomarkers can be used to optimise performance, informing tweaks in training, workload, nutrition, recovery and more.

Irish company Orreco has been at the vanguard of bio-analytics for almost two decades, ever since a student called Brian Moore, now the company’s CEO, became fascinated by biomarkers and their potential within sports performance.

Now the company works with top Premier League clubs, like Liverpool and Newcastle United, as well as teams in the NBA and NFL.

Dr John Hill, now the Head of Performance at Al-Ettifaq in the Saudi Pro League, worked closely with Orreco during his time as First Team Fitness Coach at Liverpool from 2021 to 2023.

Speaking on Orreco’s Optimized Podcast last year, he explained: “When I transitioned into a role within the first team (in 2021, after three years with the club’s Academy) I was less responsible for training prescription and more for helping to assess how players were coping with the training schedule.

“My main focus was providing something that would give us a further indication of how ready a player was to cope with the next stimulus, the next game.

“The challenge for me then was ‘what’s going to give us actionable data?’ The biomarkers give us an indication of types of fatigue. You don’t need to go in to tell the player that they’re knackered, you need to go to play with a solution of ‘these are the things that are going to allow us to help mitigate and neutralise that inflammatory response in this specific way.’”

How the biomarkers are collected

Marc Cleary is the Senior Sport Science Lead at Orreco and has been working for the company since 2018.

He describes a biomarker, in layman’s terms, as “a metric that provides information about a physiological system.”

The “gold standard” of blood testing is intravenous blood draw – inserting a needle into the vein and filling a tube. Orreco’s Advanced Analytics Service is a full blood draw giving a review of more than 50 biomarkers.

These provide information related to oxygen transport, immunology, biochemistry, hormonal drive, nutritional status, muscle damage, inflammation and more.

A club will generally send their blood samples to their partner lab before forwarding the results in PDF form to Orreco, who then upload them to their system. This has historic data for the players loaded onto it, giving an understanding of where they fall based on a reference range, but also where they have fluctuated.

We had all the analysers out on the bench tops, where players would come in and be sampled, supported by a couple of members of staff.

John Hill

Full blood draw is “the most rigorous, robust and accurate testing,” Cleary explains, but “it doesn’t align itself very well to performance reviews.”

“The problem with intravenous draw is that it’s very invasive, with a big needle going in the vein,” he adds. “Not many people like that. It’s also quite expensive per draw, because you’re getting a lot of biomarkers, and the sample has to be sent off to a lab.

“So it takes a bit of time, maybe a week, to get all the results back.”

This is why clubs typically limit intravenous full draw to four or five times per season, usually including pre-season and the end of the season, while augmenting with a more regular ‘point of care’ test. This is done with a pin prick to the ear or finger.

“Point of care means table-top immediate result analysers,” Cleary says. “The blood sample then doesn’t have to be sent to a lab – it can get processed there and then.

“The collection process is 60 seconds or less. We collect a minimal amount of blood – 140 microlitres, which is about half of the ink vial in a Bic pen.

“With the intravenous draw, you collect a vial of blood. Most standard tubes hold between 2 and 8.5 millilitres and you might collect three to five of them on a good collection.

“The point of care test enables us to get an understanding of the stress and recovery capacity of the athlete multiple times per week, which is a huge plus in a performance setting.”

At Liverpool, Hill was “very fortunate to be at a top European club where we had a small laboratory set-up in what was the anti-doping room.”

This is where they did the point of care tests.

“We had all the analysers out on the bench tops, where players as they were coming through to the treatment room would come in and be sampled, supported by a couple of members of staff,” he said.

“We eventually got to the point where Medical Assistant Lynsey (Ahmed) would run those tests, so that would free me up just to sample and communicate with the players, again supported by some of the other fitness staff.

“We had match day plus one, plus two testing, and then we had follow-ups with players that we either an interest from a medical point of view, or a training load point of view, or who were raised from a flagging point of view.”

The biomarkers

While full intravenous draw can provide information on more than 50 biomarkers, the point of care test focuses on three.

“The markers that we’ve selected are very, very robust physiological parameters,” Cleary explains. “They’ve been researched thoroughly for repeatability research, for sensitivity research, for analytical and biological variation. So they’re very, very consistent, reliable and repeatable markers.”

The three are pro oxidants and antioxidants, which fall under the umbrella of oxidative stress, and High-sensitivity C-reactive protein (CRP).

“The pro oxidants are primarily influenced by training load,” Cleary explains. “So you’ll see an increase with stress or additional load that the body’s under.

“It can also be increased by psychological load – stuff like altitude, heat, pollution. If they’re chronically produced they’re bad, because they will eventually overwhelm the other systems.

“If that sustains, we know the probability of injury and illness is going to continue to increase. Thankfully, we have a system to defend against it, which is the antioxidant capacity. That’s primarily influenced by nutritional intake, but also stuff like aerobic fitness, sleep quality, recovery practises, good hygiene. All that will increase the circulating antioxidants.

“Their job is to go around and scavenge for these pro oxidants and keep them in check. So the ratio of the two determine the overall oxidative stress.

“Managing training load will help bring the pro oxidants down; or increasing the nutritional and recovery practises will increase the antioxidant capacity.”

The High-sensitivity C-reactive protein is a marker of systemic inflammation.

“In simple terms, if I cut my arm, inflammation is going to swarm that area and help recover that cut,” Cleary says. “It’s an immune response to help recover that injury, so it’s a vital component.

“But if an athlete is chronically inflamed and showing an inability to resolve that inflammation, that’s an unhealthy system and we know there’s an issue that’s occurring and maybe they can’t sustain the demands they’re currently being placed under.”

Analysis

The final part of the jigsaw is analysis.

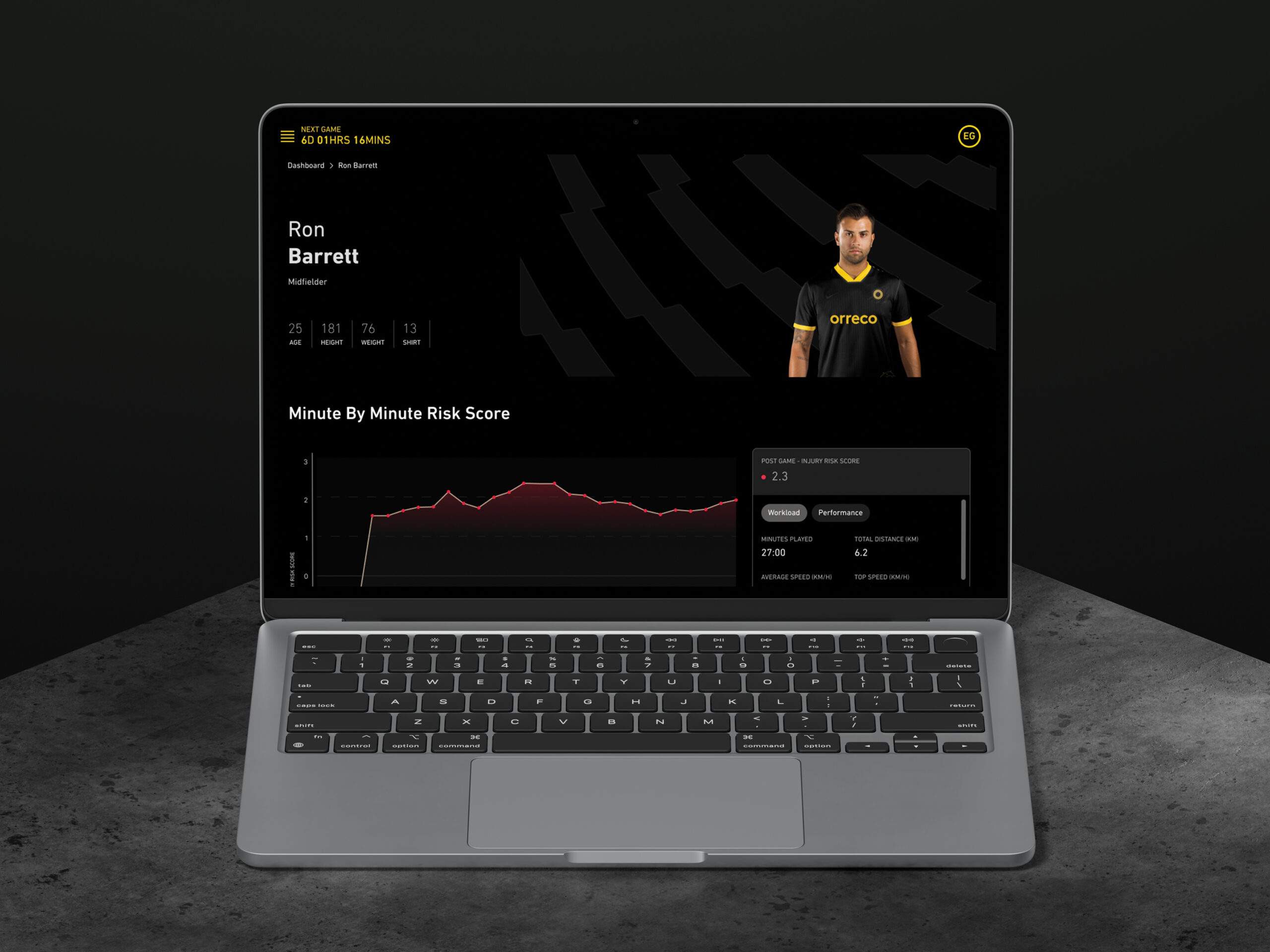

The biomarker data is uploaded to Orreco’s software platform, Te@m, and individualised results are provided for each athlete using a reference range.

AI is brilliant at being able to quickly analyse the athlete’s historic data and also bring in a range of other metrics, including GPS, heart rate and sleep to provide full context.

There is also a wellness questionnaire module and a female specific menstrual cycle management module.

“We also have medical notes on the platform, and return to play,” explains Cleary. “Then we have an analysis and reporting module. The AI goes through all of this and the goal is firstly to speed up interpretation and also see what stress is occurring from the objective blood markers.

“It can then go and source if there’s anything unusual in their GPS work or whether they have slept a couple hours less or if there has been a rolling disruption.

“Then the athlete and coaching staff can say, ‘Okay, show me their CRP values over the last two weeks.’

“You can then have the AI looking at a specific database of research material to pull the appropriate research-backed strategies and interventions that can be used for certain occasions and situations.”

Cleary has weekly contact with most of Orreco’s client clubs, and more regular contact with heavier users. There’s also a specific data and content portal for athletes called @thlete, recognising the fact that this is their data.

“The player can get into the app through their phone,” Cleary explains. “This is a new development, so the player can access their data at any stage as opposed to having to go to their club and say, ‘Can I see my blood work?’ It’s all there.

“Everything is there for them, serviceable at any time, because it is their data.”

They can access their data when they are with their international team, or if they move to a new club – and can even have all their data deleted if they so wish.

Club perspective

Communication with players is key, as Hill outlined on the Optimized podcast.

“Early in the process, there’s skepticism about what it’s going to do,” he admitted. “You’re working with players that are constantly being prodded and poked, things are constantly demanded of their time, and here you are coming in with a needle and a small kidney tray of consumables, saying, ‘I’m just going to start pricking you almost on a daily basis’.

“You’ve got to sell what’s in it for them. I remember having a really good conversation – quite a tough one – with a senior player, when I was put on the spot in the medical room about what’s this information was going to provide, what we were going to do with it.

“‘Is it going to stop me playing games, because if it is, I’m not up for that.’ I really had to go in and share all the information and all the due diligence that we’d done in the background and what we thought it would provide, how we thought it could help.

“And in the end, that finished really well. I wrote down a great little point: he said if it’s important, it’s important all the time. And I really lived by that – we’re not going to roll it out this week and go a month without looking at the data.

“That’s why we got through such a large number of tests and why it became a key part of my role there – of getting that data, interpreting that data, and most importantly liaising with the players and the coaches in order to try and mitigate some of the things we found.”

The biomarker data and analysis was always shared with the players themselves.

“The way I viewed it was, ‘Yeah, I’m taking this sample and generating the data, but ultimately it’s their data, it’s their biology.’ So if they want to know what it is, then it has to be shared.”

The way in which the data was shared – and the way in which things were said – was key as well.

“You might have a player that’s presenting on a number of measures in not the most favourable way, but you don’t want to compromise their feeling, you don’t want to give them any negativity prior to going into the competition,” Hill said.

“So how we framed a lot of the recommendations and conversations around what the data meant at different points was key. A lot of the terminology that we used: we would take out things like flags, wouldn’t talk about divergent profiles, but would talk more about change.

“‘We’re looking to include a few things to optimise your performance to bring you to a level where you feel at your best.’ It wasn’t coming in with a negative connotation of, ‘This is bad and we need to do something about it.’

“You don’t need to tell a player on match day plus one or plus two that they are tired, because if they’ve given everything in a game day, they’re going to be. They’ll say: ‘I know I’m struggling today, so I didn’t need to give you five minutes of my time and a blood sample for you to then tell me that I’m struggling.’

“It’s like, ‘Okay, here’s the information that it’s given us, and my take on it is this is the specific thing that’s going to help.’

“You don’t need to go in to tell the player that they’re knackered, you need to go to play with a solution of ‘these are the things that are going to allow us to help mitigate and neutralise that inflammatory response in this specific way.’”

- Marc Cleary and Dr John Hill will be hosting a special webinar, ‘How top clubs leverage blood data’ on Tuesday January 13th at 6.30pm UK. To book your place, click HERE.

Follow Us

For latest updates, follow us on X at @ground_guru