Written by

Harrison Gilkes

November 25, 2025

Awareness, anticipation and decision-making are some of football’s most important qualities, but how often do we, as coaches, specifically train these skills?

This is what Dr Jamie Taylor and I set out to explore when we conducted a two-part intervention-based study aimed at developing the perceptual-cognitive skills of Category One Under-18 midfielders.

There were two parts to our study:

- Conducting simulation interviews with former Premier League midfielders to generate insights into the cues and strategies that expert players use when navigating complex in-possession scenarios. We wanted to know what cues they see, what these cues mean and how they can be used to solve in-possession scenarios.

- Taking these cues and strategies, we explicitly coached them to eight Category One U18s midfielders over a five-week period. To evaluate the impact of the coaching programme, we measured and compared the performance of the U18 midfielders across five U18 Premier League South games, both before and after the coaching programme.

This study took place on the pitch rather than in a lab, which addresses one of the largest limitations found in perceptual-cognitive research to date. Furthermore, the study investigated how expert players use perceptual-cognitive skills, contradicting a significant portion of existing literature which has used mostly novice players.

Here’s what we found:

Part One: Learning from the best

We wanted to ensure the coaching programme was informed by expert knowledge, so we conducted Applied Cognitive Task Analysis (ACTA) simulation interviews with three former Premier League midfielders.

Each of the players interviewed had made more than 100 Premier League appearances. For their interviews, each anonymised player was shown video footage of them receiving the ball under significant opposition pressure and asked questions intended to generate insight into the cues they had seen at the time, what these cues meant and the strategies they used to solve the situations.

The interviews ranged in length between 50 and 90 minutes and generated two common themes:

- Creating Doubt.

- Manipulating Time and Space.

Part Two: The Explicit Coaching Programme

My role as Lead Professional Development Phase coach at Reading enabled me to coach these themes and their related cues and strategies to U18s midfielders within a Category One Academy.

Over a period of five weeks, we delivered 25 on and off-pitch coaching sessions to players within their typical footballing schedule. An explicit coaching approach was adopted throughout the coaching programme, with player attention guided towards the critical cues within practice activities. Direction was also given on how to interpret and act upon these cues in alignment with the expert insights.

Below is an example of a section of the coaching programme delivered to players, highlighting how practices were created, adapted and progressed across the five weeks.

One of the expert players who had been interviewed in Part One explained how they would create doubt in their opponent (one of our key themes) by using the shadows of opposition pressing players. They said: “I’m playing in the opposition centre forward’s shadow.

“I’m not getting high, where the pass is longer into me, because if it is then it gives the guy pressing more time to jump me. Instead, I’m just behind their players that are pressing our defenders.

“I’ve got myself time now, because I’m far enough away from the player that is pressing me and he’s never going to come up that early before I have received the ball. Even if he wanted to press me the distance is just too far for him because I’m playing in the shadow of the (opposition) front four.”

This quote helped us to identify the key cues required when devising representative practice activities to support players in creating doubt.

The video above shows the first practice activity used to develop the players’ ability to create doubt through using opposition shadows. The footage has been filmed using a drone and then telestrated.

Whilst the practice is unopposed, the relevant stimulus of an opposition pressing player and their shadow is still present. Player attention was directed to the opposition pressing player, with guidance given to match their pressing speed and timing.

As you will see, the semi-opposed player (in yellow) did not press each time, helping us to see whether players were actually identifying and correctly interpreting the cue of a pressing opponent. We selected an unopposed activity for this first practice as we wanted players to both focus on and explore the key cue of an opposition pressing forward, without the distraction of additional stimuli from a normal game.

The second practice activity incorporated live opposition, yet in a simplified manner. The pitch was split into thirds where players played 1 v 1 or 2 v 2. Player attention was again explicitly directed to the opposition pressing player and the timing and speed of their pressure.

To manage the complexity of this activity, pressing players were locked into their third, while in-possession players could stay in their zone or drop into the one below them. The intention of this was to incentivise in-possession players to use their opponent’s pressing shadow by leaving their zone where they would not be pressed or followed.

The third practice activity demonstrated a further increase in complexity and game representation. A small-sided 4 v 4 game took place, with each team comprising two defenders and two attackers positioned in their respective halves of the pitch. Out-of-possession players were locked to their halves, while in-possession players could move anywhere.

Similar to practice two, this encouraged in- possession players to use the shadow of the pressing opposition attackers to get away from their opponent defender who could not follow.

The above examples highlight how the practices increased in complexity as the players became more capable of recognising and acting upon the relevant cues from the environment. If players struggled excessively in a particular session, we repeated that same practice again or cycled back to a simplified version of the practice.

Matches

To evaluate and understand the impact of the coaching programme, we measured and compared the performance of the U18 midfielders across five U18 Premier League South games, both before and after the programme. The players faced the same opponents both before and after the practice activities to make the comparison as fair as possible.

We wanted to see whether there was an increase in the players’ ability to impact games in-possession: Did they receive the ball more? Did they progress the ball more? Did they surrender possession less? Were they better able to anticipate second balls or intercept opposition actions?

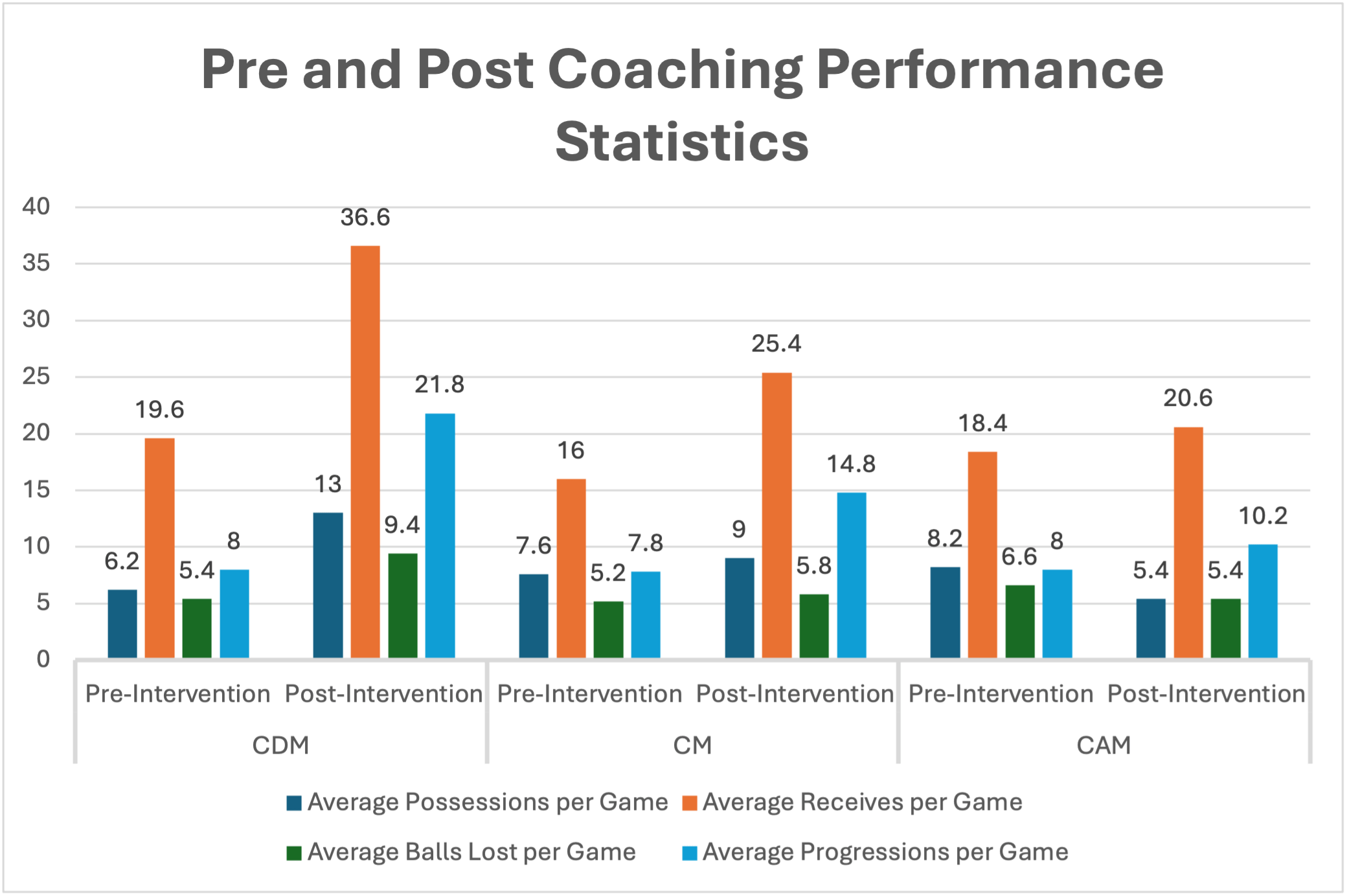

For each game, players’ actions were analysed according to their midfield role — pivot (CDM), central midfielder (CM), or attacking midfielder (CAM). The results show that the players made clear improvements in how effectively they progressed and managed possession following exposure to the coaching programme.

The biggest gains came from the pivots, who were not only more involved in play, but also successfully progressed the ball more often. Central midfielders showed similar improvements, albeit to a lesser degree. Attacking midfielders remained largely consistent with their performance before the coaching programme with no significant changed noted.

Conclusions

The findings of our study suggest explicit coaching can be beneficial in supporting the development of perceptual-cognitive skills in male football players. The study suggests that coaches should work with players on their perception of critical cues and subsequent opportunities for action.

Research investigating scanning and visual exploratory activity has been crucial in highlighting the importance of awareness in successful performance. Inadvertently, however, this may have encouraged coaches to over-value what THEY can see, rather than what their PLAYERS see.

A player might be looking or scanning, but what are they actually SEEING? For some coaches, scanning has become the goal, whereas, in reality, it is just a proxy for the underlying perceptual-cognitive processes.

Our study has illustrated the possible positive impact when coaches move beyond what can be observed behaviourally and also investigate players’ perception and cognitive processes. As coaches, we don’t want players to just look, we want them to see.

The interviews conducted with the former Premier League midfielders in Part One provided insight into the most critical moments of high-pressure scenarios that truly stretch player perception and action. Information of this nature can support coaches in developing sessions that truly represent the game.

As such, this study encourages coaches to value and lean on current or former elite players to help inform practice activities and coaching information.

Next steps

Our study is currently in review for academic submission, a process that we hope will take place in the coming months. For more information, get in touch via my TGG Personal Profile:

Harrison Gilkes is a TGG Member. You can see his Personal Profile HERE

To find out how to become a TGG Member and build your own Personal Profile, click HERE

Follow Us

For latest updates, follow us on X at @ground_guru