Challenging the concept of the 'genius manager'

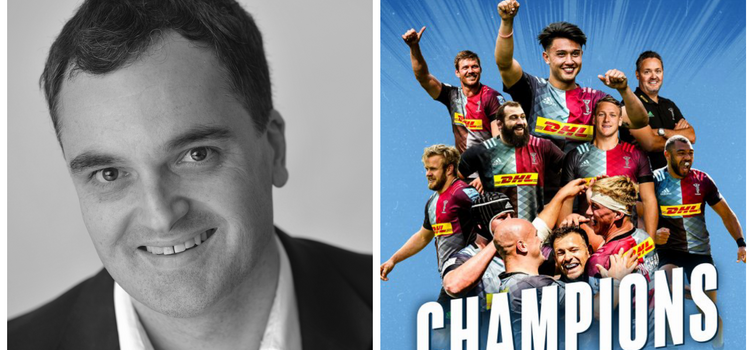

Owen Eastwood (left) says teams can learn lessons from the success of Harlequins last season

Written by Simon Austin — September 28, 2021

WHEN Harlequins Head of Rugby Paul Gustard left by mutual consent in January - with his side lying seventh in the table after losing four of their first seven games - they decided not to replace him.

Instead, a coaching team of Jerry Flannery, Nick Evans and Adam Jones was put in place under General Manager Billy Millard, who had been with Quins since 2018.

Perhaps this decision was made easier by the temporary removal of relegation, but the results were remarkable, nonetheless. Suddenly unshackled, Quins went on an amazing run that eventually saw them crowned champions at Twickenham in June.

And not only that, they did so by playing a cavalier style of rugby many had deemed impossible.

“Harlequins have redefined how to play,” enthused former England back Austin Healey. “If the Harlem Globetrotters played rugby, it would look a bit like this.”

Their story goes against convention, because many sports, notably football, have developed a cult of the manager. As performance coach Owen Eastwood (pictured above left) says: "One of the narratives that’s interesting is the idea of the genius manager. In football there’s far too much of this."

Eastwood witnessed many of the changes at Quins first-hand, having been brought in in December 2020 to "work with the Board and reflect on the bigger picture".

Speaking on Episode #31 of the TGG Podcast, the New Zealander emphasised that Gustard was "a good guy who the players cared about". However, he added that there were clearly lessons other teams could take from the turnaround.

“When I think about Harlequins, a few things jump to mind," he said. "The first was empowering players. They (the coaching team) came in and simplified everything.

“They shortened practices, shortened meetings. They asked the players for their views. And the players bought into it and started to take ownership of it. Most importantly, on the field, they (the players) were driving it.”

The coaches and players also reconnected with a brand of rugby that the club had once been renowned for. This coincided with the piece of work Eastwood was doing about the Quins identity.

“Harlequins is, I think, the fourth oldest rugby club in the world and from the early days they attracted these really attacking backs in particular,” he said. “One of their pioneer founders was Adrian Stoop, captain of England and Quins, who believed in playing with a lot more width and pace in the early 1900s.

“That has never left them and they still have that mindset, that fundamentally we are an attacking team and love having a licence to be unpredictable. Independent of the work I was doing around defining some of this stuff, the coaches and players started to reconnect with what the authentic Quins identity was.

“They loved that; who doesn’t? How many kids play in the backyard and just want to defend? We like to have the ball, do something with it and score. So you’re tapping into something that’s just there.

“They conceded so many more tries than you’re allowed to statistically to be a champion team, but they managed to do it. The mindset was, ‘Whatever we concede, we’ll score more.’”

Quins are not alone in having thrived without a Head Coach. In his autobiography, former England cricket captain Michael Atherton recalled what happened when Lancashire's Head Coach left midway through the 1999 season.

“The first 11 were better organised in those [subsequent] six months than at any other point in my career,” he wrote. “It proved what I had long felt - that coaching is often over-rated and that with an experienced and good team such as Lancashire’s there is rarely a need for them.

“It forced the captain to engage the players more in decision-making and forced the senior players to become more actively involved. The result was that everyone had an input: decisions were more easily accepted and, therefore, more eagerly pursued.”

When Jose Mourinho exited Chelsea in September 2007, following a turbulent start to the campaign, he was replaced by Avram Grant. However, it was the players who really came to the fore.

Former Blues midfielder Steve Sidwell recounted: "I remember John Terry and the lads saying, ‘Right, we need to drive this ourselves as Avram hasn’t got the experience of the top echelons of football in terms of the Premier League. We have, and we’ll drive this’.

"I’m not saying they went against his wishes or anything. He still led the football club and the football team, but the players really drove that dressing room."

The result was Chelsea almost winning both the Premier League and Champions League. They lost the title only on the final day of the campaign, to Manchester United; and reached the Champions League final, again going down to Sir Alex Ferguson’s men.

None of this is to say that teams are better off without a manager or Head Coach, far from it. After all, we’ve all seen the impact world-class leaders like Ferguson, Pep Guardiola and Jurgen Klopp have had on their respective teams.

However, the concept of the 'Genius Head Coach', as Eastwood puts it, does seem flawed. Look at the best teams and there is usually a strong structure, good personnel in key positions and clarity of vision from the top down.

Just as all of a team's successes can't be down purely to one genius Head Coach, neither can their failings.

As Norwich Sporting Director Stuart Webber said: "You probably watched the Sunderland documentary on Netflix. When you watch that, it’s no surprise that they suffered a double relegation, it really isn’t.

"They put all their faith in one man, the manager, and as soon as it went wrong, said, ‘it must be his fault’. Why not look a bit deeper?"

The best leaders actually don't bill themselves as all-knowing geniuses, as former United first-team coach Rene Meulensteen touched upon in remembering his time under Ferguson at Old Trafford.

"We had experts in every position - technical, strength and conditioning, medical, analysis," he said. "It was like clockwork. The manager achieved the highest level of management - he delegated."

Eastwood added: “There’s some interesting research around this recently on parenting. In some ways the punchline is this: it’s not about being a genius parent, it’s about avoiding doing dumb things and screwing them up.

"You don’t have to be better than every other coach, but don’t do things that can screw a team up.

"Things that can screw a team up are things like distrust, when people aren’t clear on the gameplan and their role within it, and wild mood swings and inconsistent behaviour from leaders.”

Quins have actually appointed a Lead Coach for this season - Tabai Matson - yet the lessons of last term - about empowering players, being inclusive and playing according to their founding values - remain.

One of the other teams Eastwood works with is Gareth Southgate's England - and the Kiwi says the manager epitomises many of the same key principles that were applied by Quins.

“Gareth genuinely sees it as a player’s game," he said. “He is there to facilitate them achieving what their potential might be. It’s not about him, he’s not the hero of it, the players are the heroes of it.

“I think sometimes people get that a bit wrong, that players are pieces in a chess game that you move around and the manager is the real hero of it. His humility and experiences tell him something different.”

-1.png)