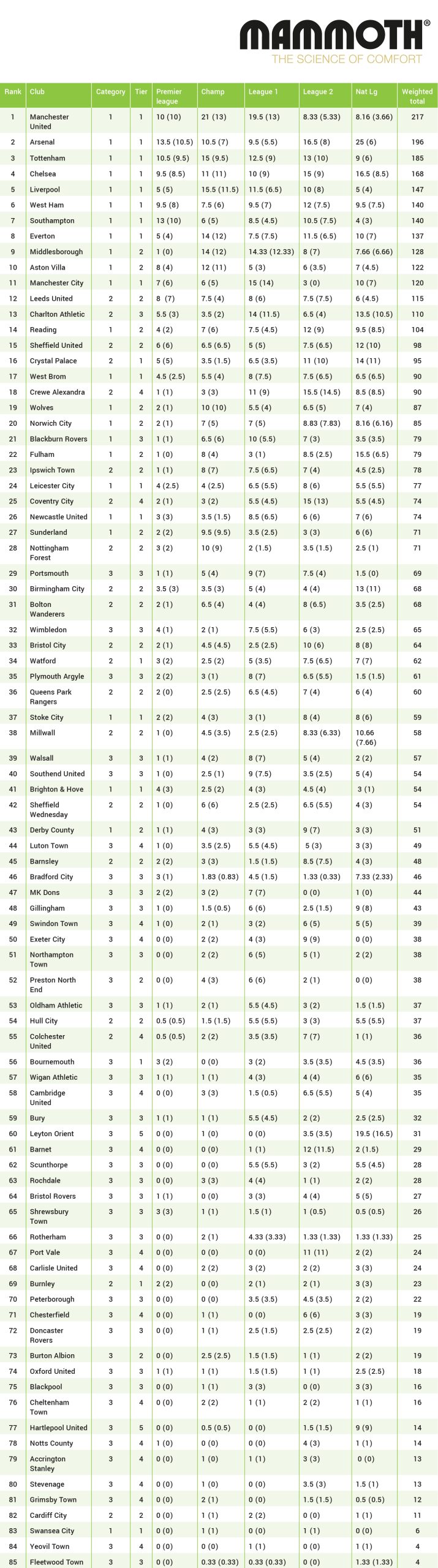

Academy Productivity Rankings 2017/18: Manchester United retain top spot

Written by

Simon Austin

December 6, 2018

Manchester United have again come out on top in our annual Academy Productivity Rankings – the only publicly available resource of its kind.

The research has been produced by Mark Crane and is this year presented in association with Mammoth Mattresses. The data is based on the Academies (Category 3 and above) attended by England-eligible players who made at least one league appearance in the 2017/18 season.

This year a weighting has been applied based on the level at which the players featured last season. You can see a full methodology below the table. The figures outside the brackets are total number of players, while those inside represent players aged 16 to 18.

Where players attended more than one Academy, the points are shared equally between the clubs.

Manchester United retained their position at the top of the table, with Arsenal again in second and Tottenham climbing above Chelsea into third.

Middlesbrough (9th) and Aston Villa (10th) are the only EFL representatives in a top 10 that consists solely of Category 1 Academies.

Leeds United are the highest-ranked Category 2 club, in 12th, with honourable mention again going to Charlton (Category 2 and tier 3) in 13th and Crewe (Category 2 and tier 4) in 18th. Coventry City (Category 2 and tier 4) are in 25th.

Category 1 Academies are again clearly the most successful overall in producing players for the top five leagues and produced more Premier League players in 2017/18 then all of the other categories put together.

However, a couple of Category 1 Academies are languishing in the lower reaches. Derby County are in 43rd, with Swansea City in 83rd – although the Welsh side have been heavily disadvantaged by the fact only England-qualified players are taken into account.

League One Fleetwood Town, who were fourth from bottom last year, prop up this year’s table, although, once again, context is necessary. The club’s chief executive, Steve Curwood, told TGG: “Our Academy is only in its third year. We are very much a fledgling Academy and can’t just turn on a switch to produce professional players – it takes time.”

Crane was moved to conduct the research last year after attempting to judge the best Academy for his son to attend.

“Unfortunately, very few useful pieces of data are publicly available to allow an objective assessment,” he said. “Indeed, the Football Association and football leagues do not even publish a list of Academies in all four categories operated by the English leagues, let alone data on how successful these Academies have historically been.

“This means that a young player and their parents have little objective basis on which to judge whether it is in their interests to join a club’s Academy, or to form a view about which Academy is likely to be better for them if they are fortunate enough to receive attention from more than one.

“In the absence of any useful data from the English football leagues, this report is an attempt to address the data deficit by retrospectively examining historical data from the 2017/18 football season, published in a variety of publicly available sources.”

Crane accepts his data is not perfect, nor as comprehensive as it could be. He adds: “It would be preferable for the leagues or the Football Association to publish audited data that could then be analysed independently.”

However, in the absence of such information, this is an attempt to fill the breach.

A Premier League spokesman told TGG: “The information clubs provide as part of their Academy audit is confidential. We will continue working with our clubs to consider further ways we can inform parents whose children are in the Academy system.”

An EFL spokesman added: “It is clear that Academies operating at different levels of the football pyramid will inevitably have different measures of success, and therefore ranking them by any single methodology fails to acknowledge the complexities of the youth development system that operates across football with each Academy having its own history, culture and ambitions for the club it represents.”

However, the EFL failed to address the fundamental question we had asked: of why they do not make their audited Academy data available to the public.

This content is for TGG Members

Join up today and get access to:

- All articles: news, interviews, analysis

- Masterclasses & Online Conferences

- Full Academy Productivity Rankings

- Club Directory: 1,000+ staff profiles

- Personal Profile Builder

- TGG Live 2024 & 2025 presentations